Canopy and Understory

In old-growth forests, gaps in the canopy let sunlight filter through, creating a diverse understory with a wide variety of ferns and shrubs. Second-growth forests tend to have closed canopies that block out most sunlight, resulting in sparser understories.

Structural Diversity

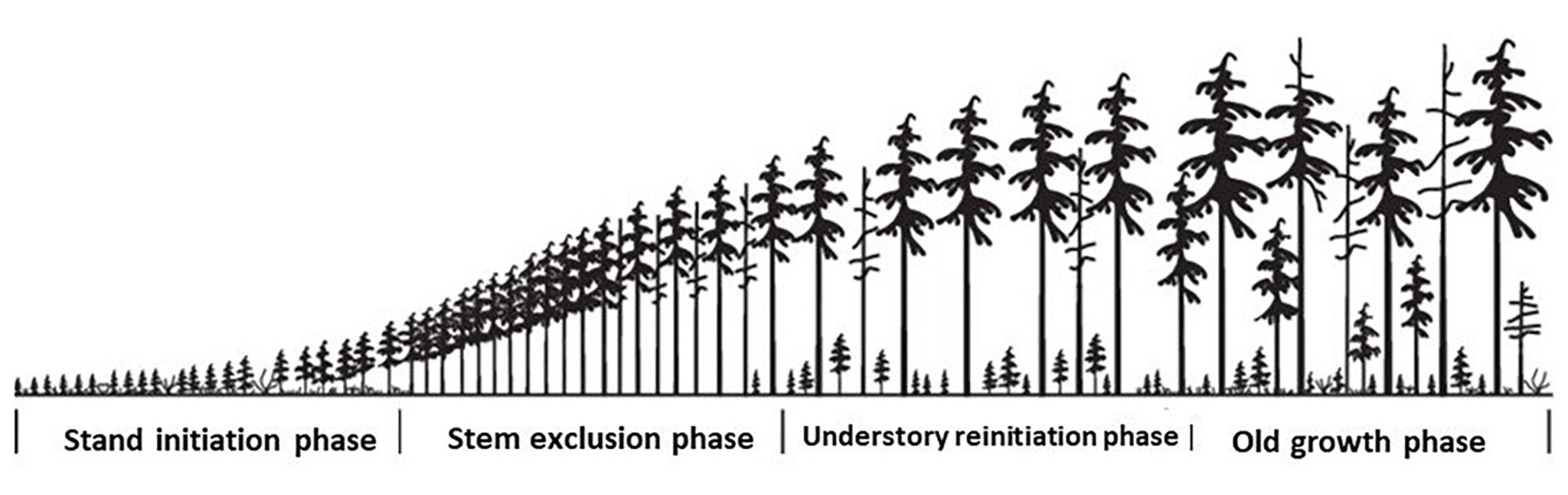

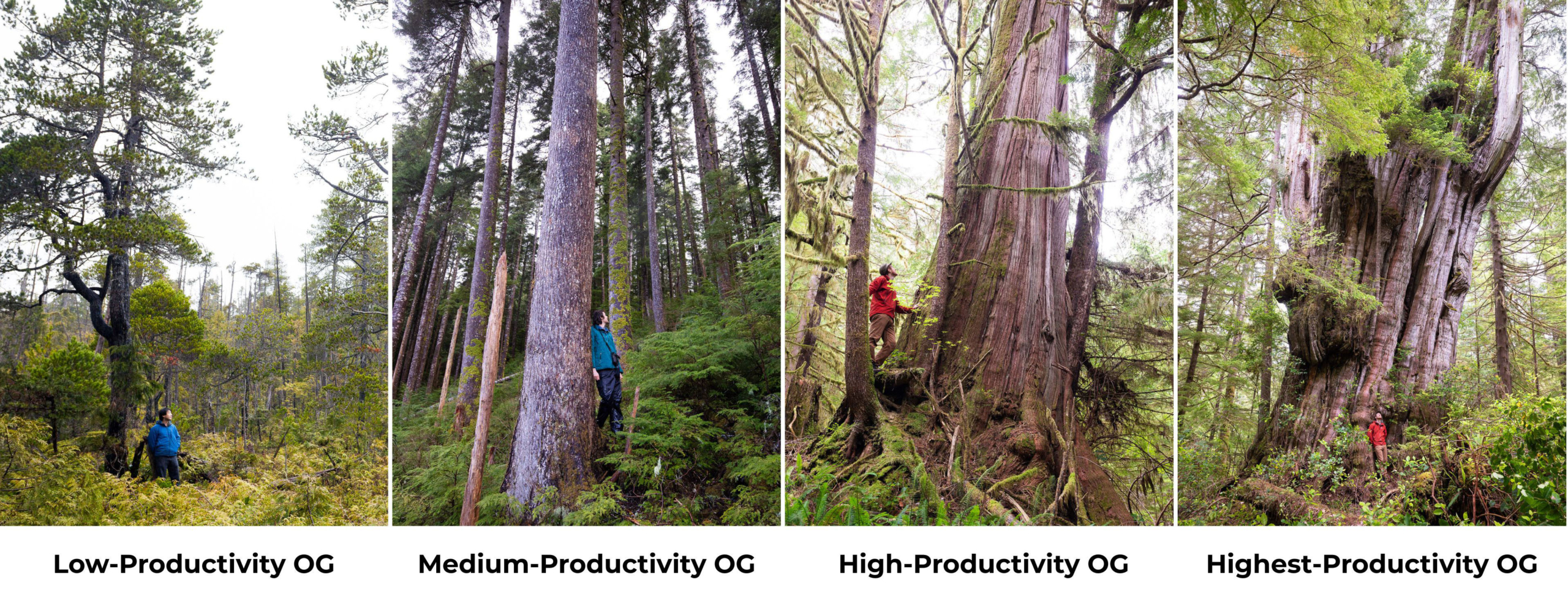

Old-growth forests are made up of trees of different ages and heights, forming multi-layered canopies. This provides habitat for species at various levels. In contrast, second-growth forests have a single-layered canopy of trees that are all the same age class and height, with much less habitat diversity.

Woody Debris

Old-growth forests are rich in standing snags and fallen logs, which provide food, shelter, moisture, and nutrients for wildlife and fungi. Second-growth forests have far less and much smaller woody debris, greatly reducing their biodiversity and habitat potential.

Epiphytes

Old-growth forests are home to large amounts of lichens, mosses, ferns, fungi, and other flora that live on tree bark and branches (known as “epiphytes”) and as a result, they support more unique species than second-growth tree plantations.

Forest Degradation

While forests can regenerate after logging, the unique features of old-growth forests take centuries to develop — in a province where the forests are re-logged every 60 years on the Coast. As a result, old-growth forests are not a renewable resource under BC’s system of forestry and are not replicated by tree planting. Watch our video comparing old-growth and second-growth forests.