Jun 12 2018

Jun 12 2018Environmentalists accuse B.C. government of fudging the numbers to log some of the world’s biggest trees

Environmentalists have accused the B.C. government of lying about the amount of majestic, centuries-old trees left standing in the province.

The National Observer reported last month that the B.C. government, through B.C. Timber Sales, had approved permits for logging that saw some of the world’s biggest red cedar and Douglas fir trees cut down in the Nahmint Valley on Vancouver Island.

The government responded, by saying that more than 55 per cent of Crown old growth forests on B.C.’s coast is protected, and that on Vancouver Island more than 40 per cent of Crown forests are considered old growth, including 520,000 hectares that will never be logged.

But those numbers are “deliberately misleading,” said Vicky Husband, a B.C. environmental activist for decades who has been awarded both the Order of Canada and the Order of British Columbia for her work.

“The forests ministry really plays with numbers, and they talk about how much old growth we’ve got left and actually, they really lie,” Husband said in an interview

“They’re trying to claim that of the coastal forest we’ve protected 55 per cent. We haven’t. That’s not true at all.”

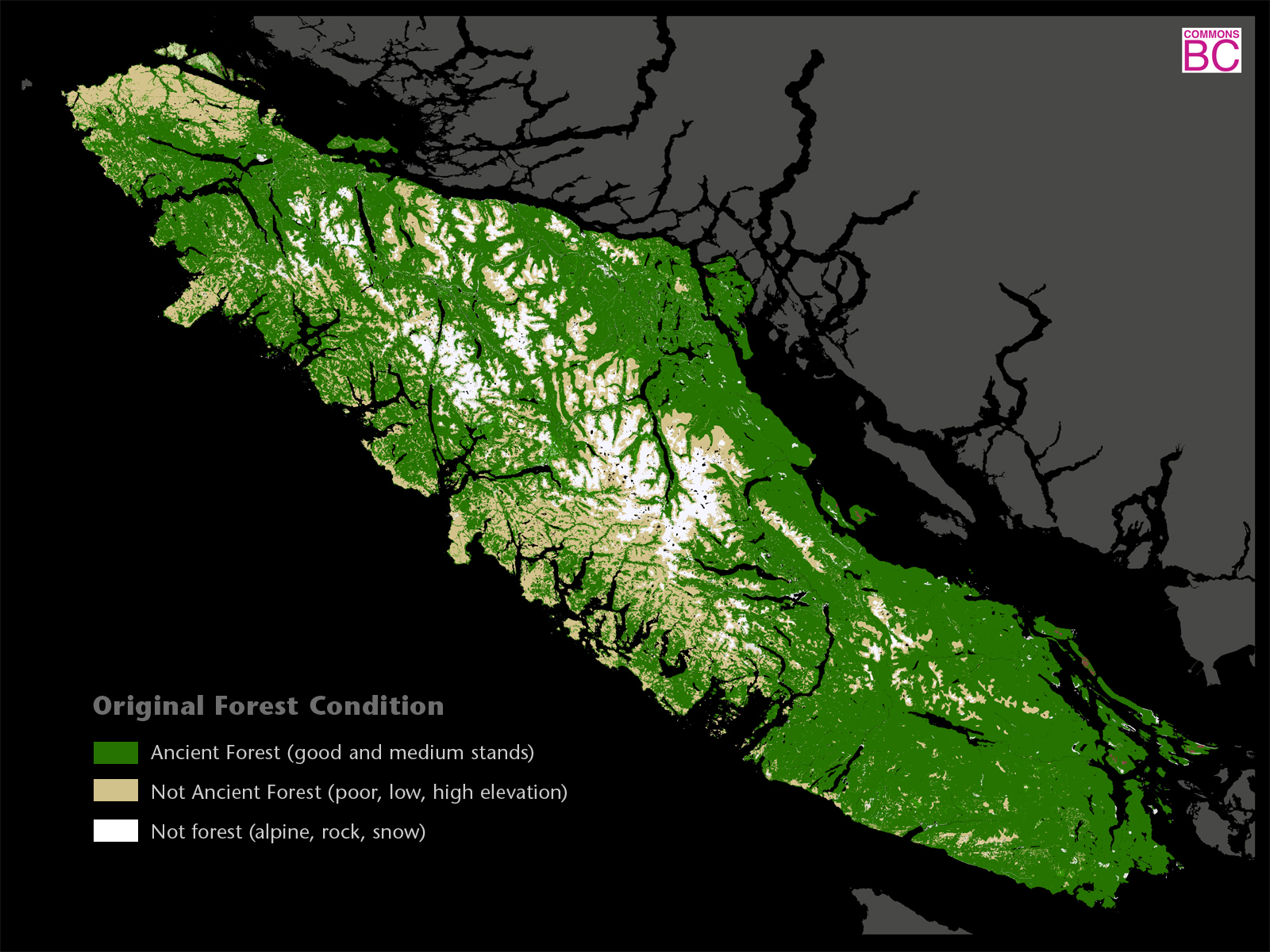

Original ancient forest shown in green. Map by Vicky Husband/Commons BC, 2018

Ken Wu, executive director with the Ancient Forest Alliance, which documented the May cutting of the massive trees in the Nahmint Valley, says it makes no sense to include the forests that will never be logged — those with small, stunted trees growing in bogs or on rocky, steep slopes — when discussing the percentage of forest that has been logged.

“It’s like including your Monopoly money with your real money and then saying you’re a millionaire,” Wu said. “It’s a disingenuous approach and it’s total spin. It’s so much spin that the marbled murrelet and the deer are dizzy.”

The marbled murrelet is a small, endangered seabird that lives in the north Pacific region and that needs coastal old-growth trees for nesting, a B.C. Ministry of Environment document shows.

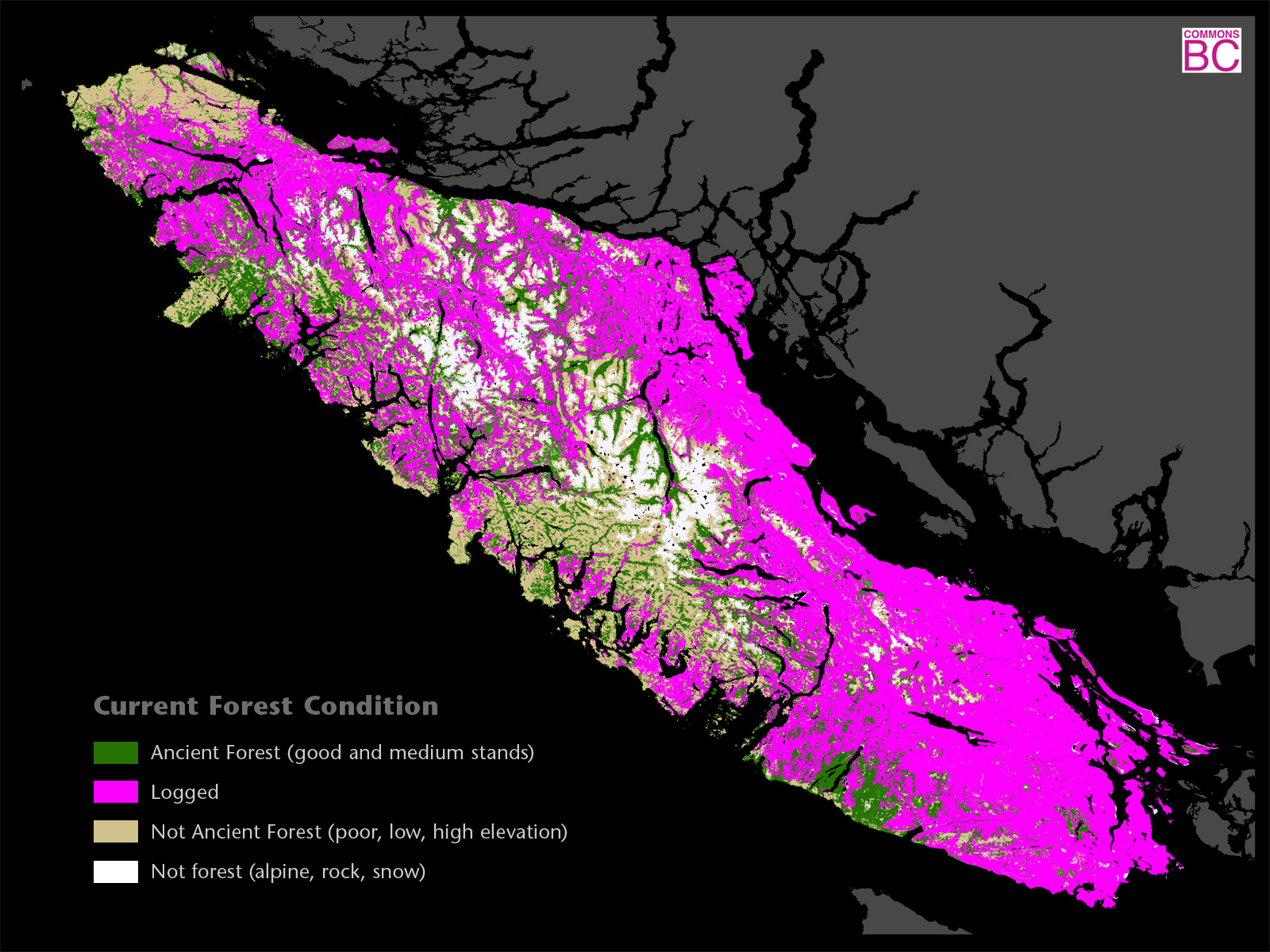

Remaining ancient forests shown in green, logged areas in magenta. Map by Vicky Husband/Commons BC, 2018

Wu also takes exception with the government taking private lands out of the equation, even though the government regulates what can be logged on those lands. Also, so called low-productivity forests, those that would never be logged, should not be counted in the total, he said.

“Otherwise it’s just complete spin, precisely designed to make people think there is no problem, that there is a lot there and a lot that is protected, which is total f***ing bull****,” Wu said.

“If the NDP government doesn’t want to continue the war in the woods, they have to stop the spin.”

B.C. government is masking an ‘ecological emergency’

Jens Wieting, a forest and climate campaigner with Sierra Club BC, made similar arguments about how the government misrepresents the numbers.

“They are masking the problem, the ecological emergency,” Wieting said. “By allowing continuing logging in these small, intact areas, that’s like burning down libraries, because we know, based on science, that we are losing a web of life that depends on these old growth forests and that’s the responsibility of the current government.”

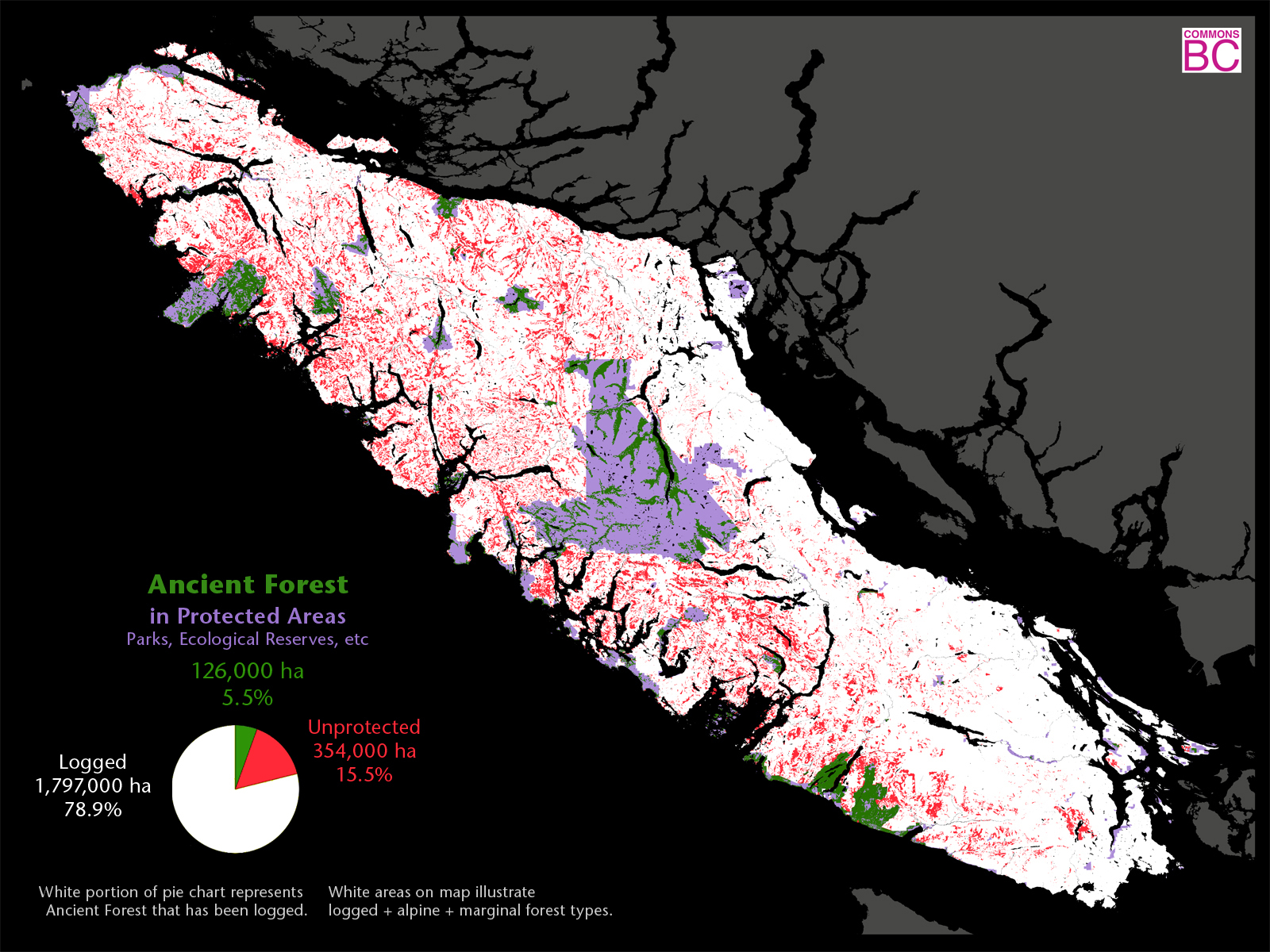

Most ancient forest is not protected, shown here in red. Green indicates old growth under protection. Map by Vicky Husband/Commons BC, 2018

Ministry of Forests responds

The B.C. Ministry of Forests says there are about 55 million hectares of forests around the province, of which 25 million hectares are considered old-growth and four million hectares are protected.

When asked specifically about what definition of old growth the province uses and whether low productivity lands are included, the ministry said “old growth is consistently defined as productive forest, or forest management land base, so swamp, scrub, bog, alpine forest, etc., are all excluded from the province’s calculations.”

Even low productivity sites have larger trees, the ministry said in a written statement, adding that one such site in the Sproat Lake area has a 252-year-old, 22-metre-tall tree.

“By law, a specified amount of the forests that reflect the definition of old growth must be retained to meet biodiversity needs,” the ministry said in its statement. “Generally, the approximate age at which old growth characteristics and structure are apparent in coastal ecosystems is 250 years, whereas Interior ecosystems are 140 years.”

The Forest and Range Practices Act and its regulations are the main set of laws governing forest practices, the ministry said.

Private land covers about one-quarter of Vancouver Island and the province doesn’t include it because it says it has “very limited jurisdiction over private land harvesting.”

When asked specifically how much of the province is protected, the ministry said 15.8 per cent of the Crown land in the province is protected, including legal old growth management areas, which make up about two per cent of Crown land.

“Old growth management areas, wildlife habitat areas, ungulate winter ranges, and ecological reserves are additional areas that contain old growth protection measures in addition to parks,” the ministry said.

B.C. government may lose social license over logging, forestry dean says

It’s not just the government and the environmentalists who disagree on how to classify forests. The problem of defining exactly types of forests should be considered old growth is complicated, said John Innes, professor and dean of the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia.

“This is actually quite a big debate that is going on internationally right now,” Innes said. “People are struggling with this and trying to work out how to talk about this and how to define these different types of forests.”

When Innes hears the term old-growth, he envisions large, old trees – like those found in Cathedral Grove, a provincial park on Vancouver Island that contains an ancient Douglas fir ecosystem. However, technically, he says, the government’s use of the term is not wrong.

“In boggy areas, the trees are so widely spaced and so thin and spindly that they’ve got no commercial value, so they’re not going to be harvested anyway, but that doesn’t mean to say they’re not old growth,” Innes said.

At the same time, he says B.C. Timber Sales should stop issuing licenses to cut down massive, old trees on Vancouver Island except in exceptional situations.

“As a general principle, on Vancouver Island, where there is now a limited supply, … we need to be careful and steward what’s left,” he said.

Innes has also heard that First Nations people now have difficulty finding trees big enough to make canoes.

Innes first learned about the big trees being cut down in the Nahmint Valley from the National Observer story and said he was surprised.

“The B.C. government is at risk of losing social license over this,” Innes said. “I do not consider it to have been a very clever move on the part of B.C. Timber Sales, but I don’t know the full situation.”

Even though the logging was legal, Innes said the move was bound to be controversial.

“I don’t think we should be cutting that size of tree down if there are alternatives,” Innes said.

The largest Douglas fir in the world, the Red Creek fir near Port Renfrew. Photo July 2016 by Ancient Forest Alliance

Besides the fact that tourists and locals alike love to visit the majestic old-growth forests on Vancouver Island, there are also scientific reasons for saving these grand old trees, Innes said.

“Every time there is some sort of a severe stress in a population, some of that population will be killed and if you’ve got trees that are 1,400 or 1,500 years old, they have survived an awful lot of those stresses, which means they must be pretty good at it,” Innes said.

“If we’re worried about the future and the future stresses on trees, those very old trees may hold the gene reservoir that we need for future forests.”

Technology is advancing so fast that soon, environmental groups may be able to count the exact numbers of large trees left in the province using drones, and track them when they are logged, Innes said.

Legislative and regulatory changes are needed now, campaigner says

The relatively new NDP government needs to make changes now, Wieting said.

“The current B.C. government is not responsible for forest management over the previous 16 years on Vancouver Island, but we have an emergency now as a result of that,” Wieting said.

“They are responsible for the losses that will happen now, because there is now so little left that species like the marbled murrelet are disappearing … and mosses, lichen and fungi that depend on old growth ecosystems. This is now getting worse as a result of climate change.

Jens Wieting, a forest and climate campaigner with Sierra Club BC, says the government’s numbers mask an ‘ecological emergency.’ Handout photo

The longer the government denies a problem on Vancouver Island, the worse the ecological and cultural damage will be, Wieting says.

“This new government continues to use the same rhetoric and the same superficial information like the previous government and that’s no longer acceptable because it’s not based on science and we are now in an ecological emergency and it’s getting worse every day,” Wieting said.

Wieting would like to see interim steps put in place, based on precaution.

“The government should stop issuing permits for old growth logging in some of these areas that I refer to as precautionary areas – relatively intact areas with significant potential for ecosystems, for species habitat for cultural value, for tourism and carbon value. We have record high carbon storage in these areas,” Wieting said.

He would also like to see legislation to protect endangered rainforest by ecosystem.

“It’s not okay to have logging continuing in some of the last relatively intact old growth areas because that means that we will have foregone conclusions, we will have a situation after the fact where there are no intact old growth forests left to consider,” Wieting said.

All that’s left is a tree museum, activist says

Husband says now is the time to stop logging the ancient forests of Vancouver Island.

“This is the last flailing gasp of the dinosaur swinging his tail,” Husband said. “If you drive through Tofino and Cathedral Grove, that’s what we have to show what those Douglas fir forests used to look like. That’s all we have – it’s a tree museum.”

Wu would like to see a land acquisitions fund so that the government can buy land from private owners to protect it from logging.

“For example, the mountain side above Cathedral Grove – the most famous old-growth forest in Canada – is privately owned and slated for logging,” Wu said. “People don’t realize that the mountainside above that stand of trees that millions come to see, can actually get logged and already has a logging road punched through it.

“The company has been sitting on it for several years because of our campaign to see where this is going to go. The government could buy that old-growth forest and add it to the park with a land acquisition fund.”

In the meantime, Wu would like to see an immediate end to the B.C. government issuing permits through B.C. Timber Sales for logging of old growth forests.

“The BC NDP can end the war in the woods, that can be their legacy,” Wu said. “They just have to do what the rest of the western world has moved to now, which is moving towards a second growth forest industry. We want them to do it sustainably, and let’s keep the remnants of the old growth for endangered species, for tourism, for the climate, for clean water and wild salmon.”

Hear, hear. I couldn’t agree more.

Read the original article here.